Fritz Haber saved the world from famine…

…Then invented chemical warfare.

This is his story.

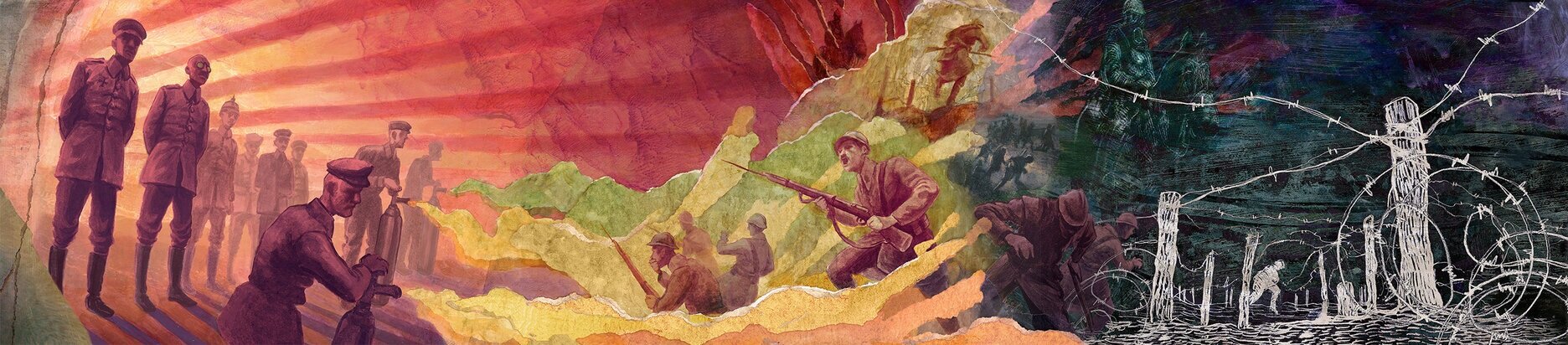

ACT I

Near the end of the nineteenth century, the world was caught in a devastating famine. The most abundant element in our atmosphere, nitrogen, was also seemingly impossible to obtain. Nitrogen is essential to photosynthesis and growing crops, so the availability of nitrogen is proportional to the amount of life Earth can sustain. As a primary source of nitrogen, manure was said to be worth its weight in gold. Spain went to war with several South American countries over access to bat guano.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Fritz Haber developed a process for pulling nitrogen out of the air and converting it into ammonia—liquid fertilizer. His ammonia synthesis process ended wars and allowed the global population to flourish. It ushered in the modern age and is among the most important scientific discoveries in history.

Upon the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, the German government approached prominent intellectuals with a proclamation to endorse the actions of the German Military. The document was known as the “Manifesto of the Ninety–Three.” While Haber chose to support his country with his signature, his friend and colleague Albert Einstein refused to sign the manifesto. The two scientists represent a vast divergence of ethics for the scientific community.

ACT II

Haber volunteered his laboratory and his expertise to help the German war effort. He combined his synthesized ammonia with chlorine to make an asphyxiating gas — mustard gas. At the Second Battle of Ypres on April 22, 1915, Haber oversaw the world’s first deployment of chemical weapons with the honorary rank of captain. The toxic gas cloud was extremely effective against the French forces on the western front. While just a test, the first gas attack resulted in 6,000 casualties

The toxic gas cloud was extremely effective against the French forces on the western front. While just a test, the first gas attack resulted in 6,000 casualties.

Haber’s wife, Clara Immerahr, was also a brilliant chemist and the first woman to receive a doctorate in chemistry in Germany. Although she worked as a laboratory assistant for Haber, Clara was opposed to using their scientific research to contribute to war.

Ten days after the first deployment of chemical weapons at Ypres, Haber and Clara attended a celebratory dinner with other German officers. That night, Clara snuck to the garden where she shot herself in the chest with her husband’s pistol. She died hours later in her son’s arms. The very next morning, Haber left for the eastern front to unleash his weapons on the Russians, despite the tragedy.

Eastern Front

Near the end of the war in 1918, Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his ammonia synthesis process. His award was extremely controversial in the scientific community. Renowned physicist Ernest Rutherford refused to shake his hand at the Nobel Prize ceremony

Fifteen Years Later

ACT III

For over a decade after the war, Haber worked as the director of a new chemistry department within the German Military—the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry. When the Nazis came to power in the early 1930s, Haber was ordered to lay-off all his Jewish employees. However, because Haber was Jewish himself, although a Christian convert, he refused. He resigned on ethical grounds in 1933.

Haber fled the Nazi regime to London and soon died of heart failure in Basel, Switerland. The Nazis used his laboratories in Germany to develop another gas, Zyklon B—used in the death camps of the Holocaust.

“Haber’s life was the tragedy of the German Jew—the tragedy of unrequited love”

—Albert Einstein

Click Through Whole Book —>